Red Sea Shipping After the Houthi Ceasefire: A Risk and Trade Flow Analysis

By Charlie Cameron

Introduction:

The Houthi rebel group have signalled a halt to their attacks on Israel and commercial ships passing through the Red Sea following the recent ceasefire in Gaza, potentially ending more than two years of global maritime disruption. Based out of Yemen, the attacks carried out by these rebels have caused significant disruption and unease in the Red Sea, one of the most important stretches of water in the world as the access point for all maritime traffic in and out of the Suez canal. Around a tenth of global seaborne trade volumes passed through the Red Sea shipping route prior to the Houthi campaign, so the recently announced ceasefire has ignited cautious optimism for a return to these levels [1].

Current Context:

Despite their announced halt on these merchant vessel attacks, the Houthi’s retain full capability to resume attacks should they reconsider their position. While exact figures around firepower remain a mystery to Western governments, they are known to possess a sophisticated arsenal including ballistic and cruise missiles and long-range one-way attack drones. Many of these weapons are supplied or developed by Iran, and they can be expected to continue supplying weaponry for future offensives [2]. Their attacks on Israel and hostilities in the Red Sea have allowed them to garner support among the Arab and Islamic worlds, build alliances with non-state actors in the Horn of Africa, and acquire support and applause from those aligned with their values across the world. Should they choose to continue carrying out attacks in the Red Sea in the future, they will not be short of support [3].

War-risk premiums also remain high despite the Houthi withdrawal, a clear reflection of low underwriter confidence of long-term stability in the region. Shipowners pay a war-risk premium on their ship insurance to protect their vessels against terrorism or conflict, and crossing a particularly high-risk area such as the Red Sea incurs an extra fee. The risk of renewed hostilities remains very real, so risk assessments continue to price in future attacks as a possibility. After the most recent round of Houthi attacks in July, the premium rose from 0.7-0.8% of hull value, to 1% according to sources at insurance brokers and underwriters. Prior to the beginning of the Houthi engagements in these waters, the premium was an insignificant 0.04%. Many insurers have also begun denying vessels with links to Israel or its allies, such as the US and UK, given the Houthi’s ideological commitment to targeting Israel and its supporters [4]. This kind of exclusion can lead to additional re-routing costs and supply-chain disruption.

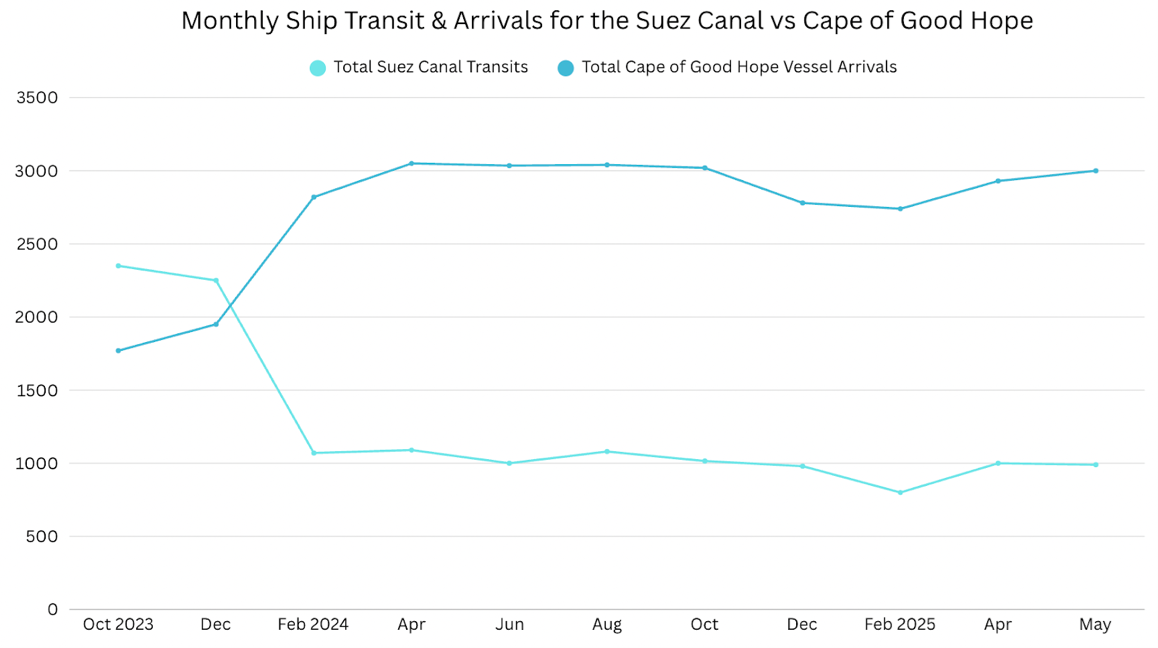

Source: UNCTAD calculations, based on data from Clarksons Research, 2025

Shown in the graph above is the number of ships transiting through the Suez Canal against those who opted for the Cape of Good Hope route. The Red sea experienced a drop in traffic of more than 41% between October 2023 and January 2024 after the initial attacks, and has not since recovered [5]. According to the IMF’s PortWatch, an average of 36 ships per day have passed through the Red Sea so far this year, as opposed to 74 for the same period in 2023 [6]. For Asia-Europe trade vessels opting for the Cape of Good Hope route, an additional 10-14 days is added onto the journey due to the diversion, causing headaches for trading and ship companies who have also had to deal with the increased operational costs, including heightened fuel and crew fees, that come with this. Despite the fragile ceasefire, some carriers have begun planning returns to Suez waters, with the CMA CGM group scheduling transits from December 2025. Crucially though, the plan is seen as exploratory and may be supported by French naval escorts, and most lines will continue to avoid the region [7].

Outlook Post-Ceasefire:

Industry analysts note that any broader resumption of Suez transits will depend heavily on insurance risk assessments, and rerouting around Africa is expected to remain the preferred route through 2026. Given the expectation that the Red Sea will remain a risk through next year, the increased burden on companies will not just be the longer voyage time around Africa, but also increased fuel consumption, crew time, and operation costs. This is likely to lead to continued freight rate fluctuation given increased strain on the ships undertaking the longer route, and even if the Red Sea shows consistent Houthi absence, carriers are still unlikely to lower their prices. These fleets have recalibrated contracts to reflect the longer routing and higher fuel use, as well as crew risk and war-risk insurance premiums, so increased prices, for both firm and consumer, are likely to remain inflated [8]. Firms reliant on global supply chains, especially those importing from Asia to Europe, can expect persistent cost pressure, longer delivery times, higher inventory‑holding and freight costs for the foreseeable future.

The persistent uncertainty around Red Sea transit despite the ceasefire means firms may look to prioritise alternative routing options and contingency logistics plans. While the Cape of Good Hope remains the safest option for carriers, it still presents the issue of increased journey time and overall cost. Especially domestic industries importing just-in-time inventory, a strategy where companies only import products as and when they are needed, such as automotives, electronics, and retail, both sea routes present their own issues. These firms may re-evaluate supply chain design by building in delivery buffers, safety stock, or even consider near‑shoring and regional sourcing to reduce reliance on long, risky maritime journeys. Longer transit times and uncertainty undermine the reliability of these products' supply chains. The rising unpredictability of maritime routes also strengthens the case for multi‑modal and flexible supply‑chain architectures, as we see robust risk management strategies becoming essential. Diversified shipping modes (to include land and air freight), long-term contracts, alternative suppliers, and better inventory forecasting will become crucial for firms who want to successfully navigate continued geopolitical uncertainty on the water [9].

There are some parties who stand to gain despite continued uncertainty in the Suez region. Ports and transshipment hubs outside the Red Sea corridor, particularly those along the Cape route in Africa, will continue to see increased traffic as vessels opting for the longer route require stops to refuel, rest crew, and conduct maintenance checks. The Port of Mombasa and Walvis Bay Port in Namibia are examples of stops outside Middle Eastern chokepoints along the African route that will see long-term growth should shipping companies permanently reroute Africa. Related businesses in these regions such as port operators, shipping-service firms, and bunkering/refuelling companies will get a boost from increased demand, benefitting local economies in these developing nations [10]. Maritime security as well as risk mitigation and insurance firms may also see sustained demand growth for their services. While piracy and isolated militant attacks on ships have occurred in the modern era, the sustained, politically motivated, and missile-drone-based campaign by the Houthis against commercial vessels is unprecedented in both scale and strategic impact. For security and risk firms, entering a new age of maritime uncertainty is great for business, and their services will become non-negotiable for shipping companies.

Conclusion:

While the idea of the ceasefire announced by the Houthi’s is positive, regional tensions, particularly in this area of the world, are too unstable to offer any real assurance. Sustained stability in the Red Sea will depend not only on Houthi restraint, but on broader diplomatic engagement across the region, including the role of Iran and the willingness of international coalitions to maintain maritime security. Even with a cessation of attacks, the structural shifts triggered over the past two years, higher insurance costs, redesigned shipping routes, and greater geopolitical risk-pricing, will not unwind quickly. Global trade is entering a period where resilience, adaptability, and diversified logistics matter as much as cost efficiency. Whether shipping patterns eventually normalise or settle into a new long-term configuration, firms and governments alike will need to prepare for a more fragmented and unpredictable maritime environment.

References: